5 Difficult Lessons Learned from One Brand’s First Documentary Series

We’d spent hours with the subject — literal hours. It didn’t seem to matter.

Our producer, Tyler Bouchard, had called this person several times to prep our shoot. They would be our guide into the company’s office. Tyler and the subject hit it off. They talked at length and excitedly about all the stories they’d tell us on camera.

The day of the shoot, our DP (director of photography) joked around with the subject, too, as he set up cameras and lights and directed the production assistant to his place with his own camera. The subject seemed at ease, smiling, warm, ready to inspire our eventual audience.

The host (that was me) sat in front of the subject, across a desk, chatting about all the lovely people I’d met from the subject’s team, and they reciprocated with more jokes and more beautiful anecdotes about colleagues and customers. It all seemed destined to be great.

“Oh, wait, are we rolling now?” they asked me.

“Ummmm yep. Yes. We’re rolling now,” I said.

And immediately, that warm storyteller of a subject became a rigid robot, beeping out slogans and jargon and completely unusable footage.

This is just all too common on a shoot. In the list below, I’ll revisit what happened next and how we solved this problem. But first, some context…

Over the last 18 months, I’ve been working with a tight-knit, lean crew to create Against the Grain, a documentary series exploring a better philosophy behind business success than the typically celebrated story. You know the one, I’m sure — winner-take-all, high growth at all costs, quarterly (or even monthly) metrics reign, and what gets lost are craft, customers, and the community. This is a scorched earth approach to business (sometimes, and too often, literally so). Yet this is the archetype for what it means to succeed — rise to the pinnacle of some imaginary pyramid, and rise fast. But scattered throughout the world are these wonderful leaders and teams which are hellbent on building something based on shared values with their customers and with the broader communities in which they participate — locally, nationally, and globally. These people aren’t less ambitious than the callous and capitalistic Zuckerbergian approach to growth. Instead, they’re MORE ambitious: how do you grow a for-profit company and use it for good, too?

This is a bold idea for a documentary series, and I jumped at the chance to host, write, and co-direct it, when the client (Help Scout) and their CEO (Nick Francis) first approached me with the concept.

But man, ohhhhhh man, did we learn a ton in making this. Today, I wanted to share five of the most powerful things that we’re keeping with us throughout the rest of this experience — and long after.

1. The real first challenge isn’t what most marketers discuss.

Yes, it’s important to have or hire the technical savvy to pull off the shoot and edit it. It’s important to understand the marketing processes needed to raise anticipation through trailers and teasers, launch to a passionate community, and grow through word-of-mouth and smart distribution. And of course, measuring the impact of your work on your brand and, just as if not more crucially, your audience — that’s always a challenge. All these things are important, sure. But they’re not THE most important thing.

THE most important thing, and therefore the first challenge to tackle, is to say something that matters. This is painfully obvious yet often overlooked. We tend to skip so far ahead in the process as to forget that interviewing smart people or talking about a set list of topics is NOT an actual premise for a series. A premise is developed through real rigor and process. A premise doesn’t just describe WHAT the show explores but also HOW the show aims to explore it. (“This is a show about X, where we Y.” This is a docuseries about business success, where we seek to replace the typical, damaging, growth-at-all-costs story of business success with a new story based on caring for craft, customers, and the community.)

Your angle, conceit, gimmick, and hook — your beliefs and evangelism of a better future — become the necessary first focus as you develop a show. Skipping it renders your project a poor investment, because you wind up creating a commodity. ATG is nothing if not an original, and I’m damn proud of that. It took hours upon hours of discussion, research, and trying stuff in written and video form to get that right — and it’s still got miles to go to improve.

2. When prepping subjects, think “access” and “participation.”

While we didn’t exactly shut down our subjects’ businesses, we did “come in heavy” for multiple days, in the words of producer Tyler Bouchard. We’re asking for serious trust that we will create something you love about your business (and, early on in the series run, we’re asking for that trust without anything to show from past shoots, as nothing was edited just yet).

When making a documentary, you’re in the trust business. You’re in the culture game. Your job is to create the right environment with your team and with your subjects to ensure they speak their minds, and speak honestly. So, part of “access” is the prep work to build relationships and ensure others not only give you permission to shoot and explore and interview folks, but they themselves become eager participants. They become eager participants in two ways. First, they participate in your planning, whether before the shoot or during. Countless times, Tyler would hear from somebody on our shoot something like, “Oh, hey, have you talked to Rick down the street? He runs this distillery which is a great partner of ours. You should see if he’ll show you around for awhile. Here’s his number…”

That’s the first way subjects participate: they share their ideas and provide new story threads for you to pull. That makes production and post-production so much easier, because you leave the shoot with richer material.

The second way others participate is by serving as great subjects — speaking honestly, sharing stories, and generally acting like human beings on camera instead of PR-approved robots. The subject I mentioned at the top of this post stiffened up because they weren’t used to being on camera. It’s not a normal feeling to be surrounded by multiple cameras, with a boom mic hovering overhead, a bunch of shockingly bright lights around your office, 3-4 strangers staring at you, checking their camera footage of you, then staring at you again. Then another stranger waltzes over and tapes a microphone to your shirt. It’s just not a normal day if you’re that subject.

That’s when you need them to feel like active participants again. As I began to see them growing nervous, I calmly coached them, directly, without pretense. They KNOW we’re on a shoot. Their problem is they’re trying to FAKE having a real conversation. I need them to have an actually real conversation with me … in a wildly fake setting. The best ways I know how to do that is to (A) ask very simple, open-ended questions, (B) overtly tell them what we’re looking to get from the interview (“our audience really loves when people tell stories, so do you have any examples of when that happened?”), and (C) ask irrelevant, personal things based on stuff in the room or stuff you know about them. For instance, this subject happened to have a drawing of a dog on their desk. Three questions into the “real” stuff, as they began to feel too stiff for a good conversation, I started asking about the dog. I watched their shoulders immediately drop. They smiled, breathed more normally, and spoke like “them” again. I could then ask the next “real” question and get a far better answer.

So, getting access to shoot properly and shoot lots of stuff is huge. So, too, is inviting your subjects to feel like participants in the project, or even their slice of the shoot. Let them in on it. You’re trying to accomplish something. Don’t play coy. Address that.

3. You need slack in the system. (It won’t just appear. It must be planned.)

Often, and especially with projects done in-house by marketing teams, we fail to build any slack into the system. Slack comes in many forms, but they all serve a purpose. For instance, you need slack in the process of selecting subjects. You shouldn’t just put someone on camera because you did a prep call with them. You should do prep calls with more people than you agree to shoot. We have a weird sense in marketing that whomever we meet or talk to must automatically be used in the final cut. I get it: nobody wants to waste someone’s time. But the best use of YOUR time — and your audience’s — is to produce the best damn final project possible. That means sifting through lots of subjects and several hours of discussions before landing on a narrower list of people and moments you wish to include in the final edit. (This American Life kills half of the stories they start reporting. HALF. That means thousands of people exist in this world who previously spoke to someone from that show, then never heard themselves in the final episode. Get used to it. That’s production.)

Another form of slack in the system that you’ll need to incorporate is the number of minutes you get with a given subject. For instance, in episode 1 of ATG, we got about 45 minutes with the company’s CEO. He was only able to meet in the board room, too. There’s no slack in that system. Normally, you need much more time than that to build rapport, to explore different moments in his life, poke down different avenues and see what lights him up (or lights you up as the interviewer and keeper of the show’s overall story).

Consider one example: the great Terry Gross, host of the NPR show Fresh Air. She’s famous for her amazing interviews. Every question has a purpose, every moment feels irresistible to the ear. However, while she is undoubtedly a masterful interviewer, one part of her mastery is that she (like so many of the great interviewers) gets more time with the subject than the final episode we hear or see. Fresh Air runs something like 40-60 minutes per interview. Terry Gross gets two hours with a subject. That’s some darn-useful slack in that system.

The last type of slack in the system I’ll mention here is your production schedule. With ATG, different episodes had different levels of slack in our production schedule. Death Wish Coffee was pretty tight, in that every day was pretty packed and fairly scheduled out ahead of time. As a result, the editing process for episode 1 lived and died with our ability to execute the plan. But the plan is always a distant echo of reality. You’re better off scheduling a few “pickup days,” which don’t include much if anything on the actual calendar — and that’s by design. They are, themselves, the slack in the system. Live on a shoot, you always notice stuff, get new introductions to people or places, find little story threads to pull that your research didn’t surface beforehand, and generally come up with new ideas in the moment. All of that requires that you have some time to shoot the unexpected. Those are your pickup days.

Yes, you’re “picking up” things like b-roll and monologues by the host and maybe extra time with interview subjects if needed. But you’re also able to address new ideas that you didn’t anticipate until you were there. You can’t do that with a rigid schedule. You need slack in the system.

4. When a series is new, start with subjects. As it grows, start with ideas.

On a live-streamed call with Help Scout’s audience, CEO Nick Francis and I talked about why we made the show together and where we hoped it would lead us. One of the viewers asked about other companies we wanted to profile, and while Nick and I both had some ideas, I realize through making the first few episodes that I should set my ideas aside for the next run of episodes.

When you first start a show, you have nothing to show potential subjects to convince them to come on board. You need access and an active participant, but you have to earn that level of trust by showing other, past projects, or perhaps by pitching the grand vision for the show and hope that works. However, you can also tap warm relationships or get introductions from your network. Additionally, when you first start, you’re not totally sure what the episodes will be like. So many elements are still uncertain and are nothing more than theory at first — from the tone and feel of the show to the way you articulate the premise each episode to the runtime to the types of moments you want to capture each time. Once you make an episode (or two or three), you have a better idea of what the thing you’re making is.

For all those reasons, when you first start a series, it’s better to lead with subjects you’d like to book — and know you can, indeed, book them. Then, those episodes start to lead to new questions about the topics you explore, and you start to hear from your audience. Your next run of episodes should therefore start with those questions or ideas that should be explored next. Rather than start with subjects and reverse-engineer the lessons, insights, or ideas they illustrate, start with topics, ideas, and questions, then go find subjects who fit.

At first, you were just trying to figure out how to make this show, and the subjects are better off being easier to book and talk to early on as a result. But over time, you aren’t trying to figure out the show — you’re trying to figure out the premise. You’re exploring the themes and ideas driving a show that you know you can make, so you should switch your focus, from any guests that roughly fit your premise, to only those that can help speak to something specific you want to explore.

5. You want to see some viewers stop watching episodes immediately, while the rest stay until the end.

The golden rule of showrunning is “get them to the end.” Ideally, everyone who starts a episode will finish the episode. That said, there are certain instances and certain people which present you with a false-negative, and it’s dangerous to react and change your work based on that data. There are certain people who don’t get to the end — and that’s a good thing.

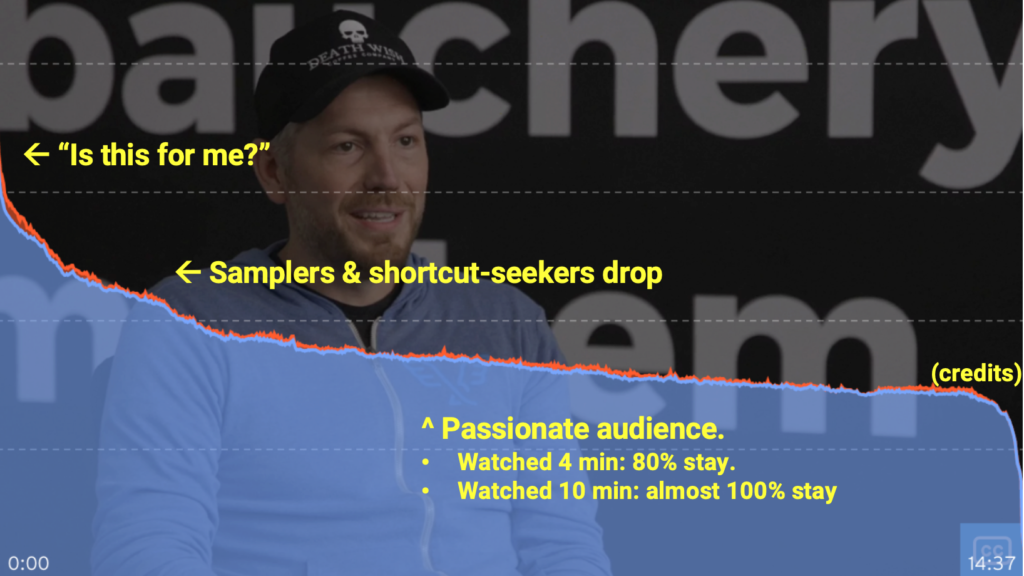

This is a look at the drop-off curve from viewers watching episode 1 of ATG, featuring Death Wish Coffee. (The full episode can be found here.)

Note the steep decline in the first few seconds, among other things…

That early, steep decline is actually something you want — if and only if it’s followed with a flat plateau of viewership. You want to use the early moments of your episode to provide a clear summary of what the show aims to explore. This is NOT a summary of the episode, but rather, the whole premise of the series. This is where you front-load your belief system, or state the problems you’ve noticed with the world and why you’re here to fix them. The early moments are like a helpful filter, which only the RIGHT audience gets through. Content imbued with your beliefs provides a helpful form of friction to build a brand. You’re not creating something that’s sorta-kinda-somewhat for everyone. You’re creating something (be that a show or your whole brand) which is VERY FOR some people and VERY NOT for others. That’s how you develop deep affinity, spark word-of-mouth, and grow in a healthy way — which we’re finding already, not only based on the public buzz the series is generating, but based on the data: 80% watch the full episode if they watch at least 4 minutes, while almost 100% finish the 15-minute episode if they watch 10 minutes.

That’s good! Our message aligns with their belief systems. The story is gripping enough that if you get into it, you want to see where it goes.

So, the early moments of drop-off don’t bug me, especially considering we have this core group that sticks and stays. I’ve said it before, I’ll say it a million times more: Great marketing isn’t about who arrives. It’s about who stays.

Additionally, I’m not overly concerned about the drop-off at the very end of the episode, either. That’s when the credits begin. (I do want to see if we can improve that, since the credits offer valuable information (like the brand which made this — Help Scout — and the link where you can watch more). So perhaps we somehow tease a final segment coming up right before the credits play, then play the credits, then play the final segment. That’s one way to ensure people stay through the credits. Regardless, it’s not overly concerning that people drop so abruptly at the very end.)

However, what I am now curious about is that group of “samplers and shortcut-seekers” dropping off. I call them “samplers and shortcut-seekers,” because they’ve decided this show and its message are very much for them — they watched through my loud, clear articulation of the premise through my voiceover and various B-roll and music in the opening moments. They got through the first filter. But now, they’re dropping off. We lose something 20% of the audience that made it through the credits, right as the story begins. There are many reasons as to why that might happen. Maybe the early moments of the story aren’t gripping enough. Maybe they aren’t given any teasers for what they’ll learn by the end of this episode in particular, after we gave them a teaser of what the whole series is about at the top.

But honestly, I’ve been around the B2B world long enough to surmise what’s happening here. These people believe what we believe, want what we want … but they want it spelled out for them.

This is NOT the vehicle for that. This is a story, a narrative, a show designed more like a travel series than a business program. There will be no exact tips and tricks written out on the screen. This isn’t about tactics at all. Help Scout is doing very many things to support that desire (like the Facebook group for the show’s fans; like their great blog). But that knowledge doesn’t show up early, and from the early moments of the story it’s clear: this is a story. It will take time, require deep thinking and sitting with big thoughts and emotions. This is not a checklist of steps you can take.

That’s not for everybody — even the folks who believe what we believe and like the idea of the show. Once they understand this episode is a commitment, they decide it’s not for them. So, since they’re the right audience, how do we keep them around? Maybe we use a little graphic that pops up. “Join the Facebook group” or “Get the strategy guide.” Maybe I should use my voiceover to better hint at what the audience will get at the very end. I’m not sure. I’m still learning.

However, what I do know for sure: When you have a core group that deeply loves a project and its ideas, you’re onto something special. Qualitative feedback is the most overlooked yet powerful data at our disposal as makers and marketers today. People responding with passion, publicly, is like those people placing a bet with their time and reputation. They’re betting that by sharing something they love, others will think highly of them, too. They want a return on the time and reputation they put on the line in order to say something to you or about you.

Now it’s on us as creators to ensure the audience gets a return on their investment. That’s a type of ROI we need to talk about more — because it leads to the ROI we want, too.

Watch all of Against the Grain right here.

Founder of Marketing Showrunners, host of 3 Clips and other podcasts and docuseries about creativity, and author of Break the Wheel. I’m trying to create a world where people feel intrinsically motivated by their work. Previously in content marketing and digital strategy at Google and HubSpot and VP of brand and community at the VC firm NextView. I write, tinker, and speak on stages and into microphones for a living. It’s weird but wonderful.

Get in touch anytime: jay@mshowrunners.com // Speaking inquiries: speaking@unthinkablemedia.com