The Green Smoothie Problem: How to Properly Sell Ideas Internally to Get Buy-In

![]()

Ever excitedly share an idea with a teammate, boss, or client that’s met with such horror or confusion that you wonder if you’d accidentally suggested clubbing baby seals?

No? Just me? Welp. Thanks for coming to my TED Talk.

We’ve all delivered an idea to someone else where we feel total conviction that it’s objectively the right path forward, and yet, we can’t seem to convince others. They just don’t “get it.” This is arguably why we created Make the Case Month here on Marketing Showrunners all November long: We want to help more marketers and marketing leaders make the case internally to marketing leadership and company executives alike that they should be creating podcasts and video shows.

Part of this is about making the case for shows, yes. But another huge part of successfully selling in ideas is to get better at the “selling in” part. Because too often, we get that pushback, confusion, or blank stares.

Why? Why does that happen? And more importantly, how can we fix the issue?

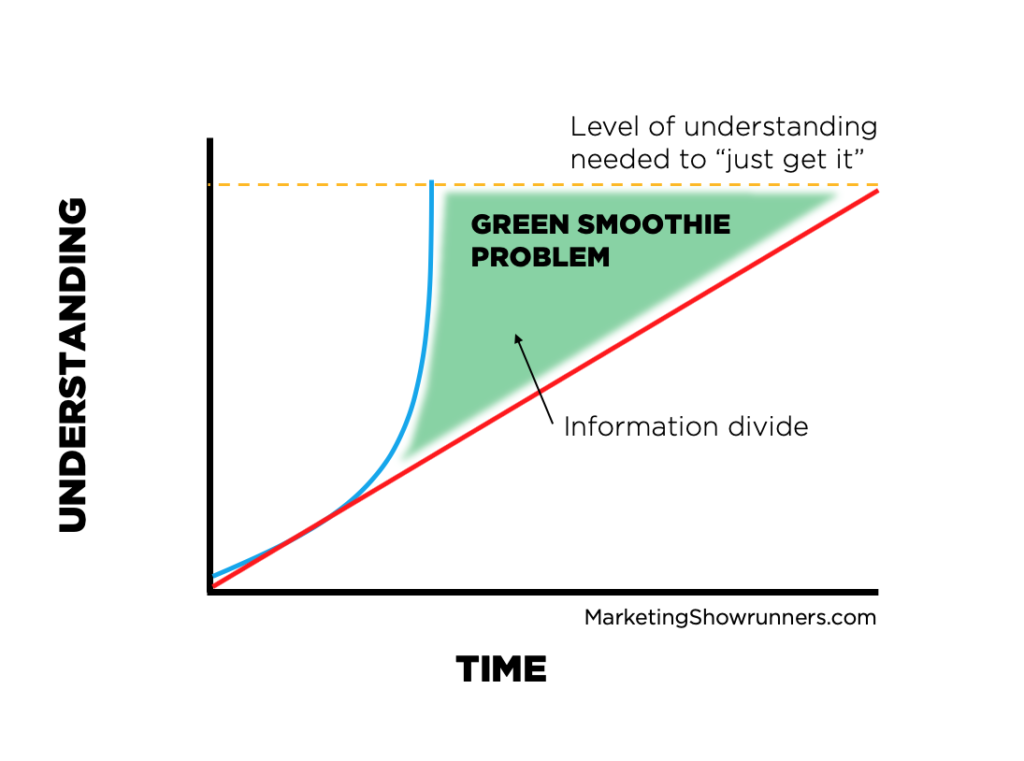

It starts with diagnosing the real problem. We assume that an executive is old school, or that we need more budget, or that our company or industry is too boring for others to get on board with the idea of making a show. We assume that and more. But the real, underlying issue is that it’s so much easier for us to understand our ideas than for anyone else to do so. In other words, every time we share an idea, we create a sort of information divide between us and them.

That divide is what I call the Green Smoothie Problem.

The Green Smoothie Problem

Imagine I just handed you a smoothie in a glass. It’s bright green. “It’s a green smoothie,” I say. “Drink it!”

How might you respond? Most frequently, you’d have one of two possible reactions:

PRECONCEIVED NOTIONS: You’d rely on your own preconceived notions to make a decision. If you’ve tasted or even just seen a green smoothie before, and that appealed to you, you might drink it. If not, you’ll start anchoring your thoughts to whatever other preconceived notions might be swirling around your mind. “Oh, I saw people at the gym drink this once. It’s like, a wheat germ or wheat grass shot, right? Gross. Not for me.” Or else, “This looks like my kid’s favorite juice. Too sweet for me. Pass.” Or perhaps, “Ah, I’ve tried all these healthy drinks before. They’re all terrible. No thank you.”

SOCIAL PROOF: If you don’t rely on preconceived notions, you look for proof that this is a credible drink. “Do people really drink this? Is this popular? Do studies show it’s good for me? Are celebrities endorsing this drink? Is there a green smoothie CASE STUDY I can see?”

Sound familiar?

Why, when I simply place a green smoothie in front of you and command that you drink it, are you reacting in one of those two ways? Because you’re looking for confidence to make a decision. Confidence comes from having the right information — which I didn’t give you at all — so now you look for your own preconceived notions, your own firsthand experiences, to draw confidence and make a call. Are they the right firsthand experiences or the most relevant to make a good decision? Not necessarily. But you need information, so you turned to your own history for that. Not a great way to get someone to try something new, right?

Alternatively, and just as poorly suited to push someone to adopt a new idea, you might have looked for social proof. This is also your attempt at drawing confidence, but this time, instead of drawing it from your own life, you’re looking to someone else to serve as a proxy for trustworthiness: popularity, studies, examples, celebrities. Again, this is not the best, most relevant way to make a decision.

Don’t Want a Green Smoothie? We Don’t Blame You

Here’s the thing though: It’s not your fault. I’ve actually put you in this position. By merely handing you the smoothie and commanding you to drink it or hoping you think it’s a good idea, I’ve jumped too quickly to the end result I want. I’ve jumped right to the idea: drink it! In doing so, as soon as I’ve started explaining my idea (poorly), I’ve put you at an information disadvantage.

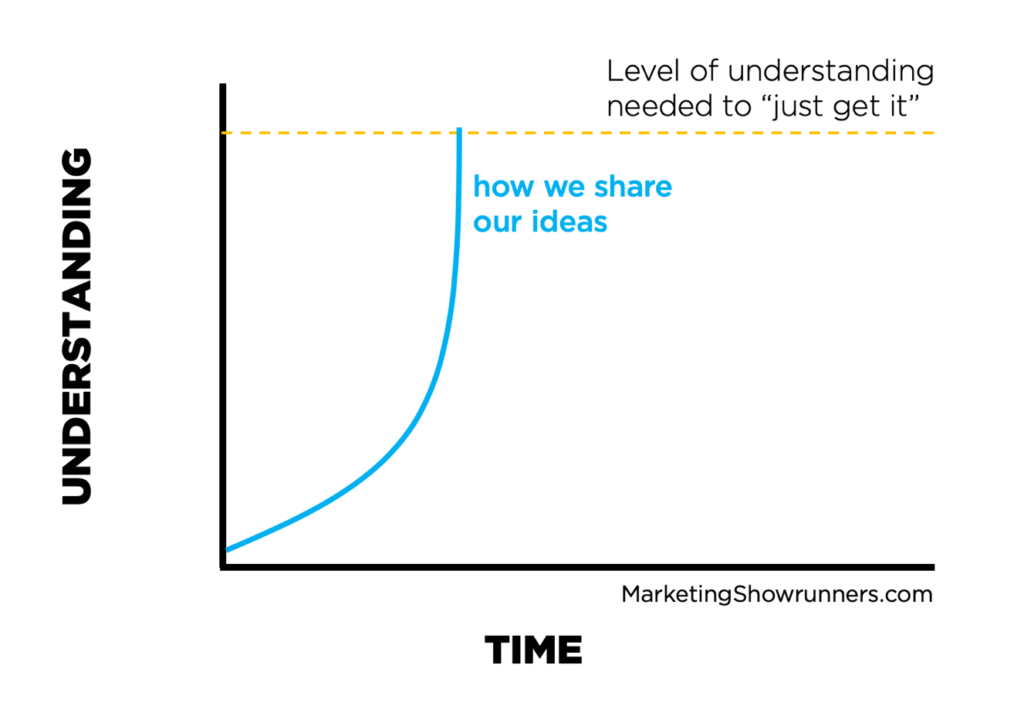

You see, this is how we present our ideas:

We too quickly share the idea. We’re already there. “It’s a green smoothie. Wanna drink it? Drink it!”

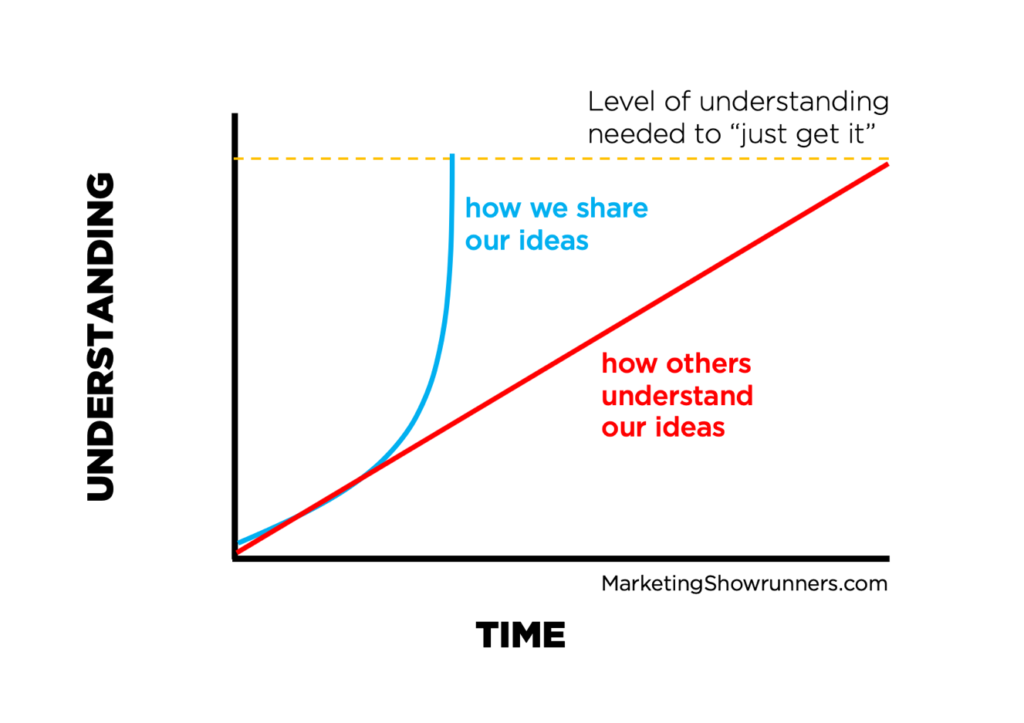

Unfortunately, while that’s how we typically share our ideas, THIS is how people understand them:

In our eagerness to sell in our idea (to make a show for our brand), we too quickly arrive at the conclusion, like that exponential curve. On the other hand, people tend to learn about ideas in a more linear fashion. If THIS, then THAT, and THAT, and THAT, and so on. They want to make the logical, obvious, best choice, and whereas we’ve gone through that entire thought process already (consciously or perhaps subconsciously and instantly), the people we’re trying to persuade are still at the beginning. To catch up, they use the best information available to them to draw confidence and make a final call.

In our eagerness to sell in our idea (to make a show for our brand), we too quickly arrive at the conclusion, like that exponential curve. On the other hand, people tend to learn about ideas in a more linear fashion. If THIS, then THAT, and THAT, and THAT, and so on. They want to make the logical, obvious, best choice, and whereas we’ve gone through that entire thought process already (consciously or perhaps subconsciously and instantly), the people we’re trying to persuade are still at the beginning. To catch up, they use the best information available to them to draw confidence and make a final call.

We think our job is to share our idea. It’s not. Our job, and any successful explanation of new ideas, isn’t to share our ideas. It’s to share why our ideas should exist.

In other words, rather than allowing others to default to what they feel is the best information to gain confidence quickly (preconceived notions or social proof), it’s our jobs to hand them better information to make better decisions — not just hand them better ideas.

We need to share the path TO the idea, not just the final idea — and do so at a speed and cadence that others logically follow.

We need to close that information divide.

Walking Down the Idea Road

So how do we do that? We can rearrange the order in which we share our thinking en route TO the idea. We can share why our idea should exist, THEN reveal the idea … rather the leap to the end and lose people.

Back to the smoothie metaphor. Rather than say this:

“It’s a green smoothie. Wanna drink it?”

…I can say this:

“Remember last week, when you told me you wanted to be healthy? And then you joked about all those foul-tasting health drinks? Well, here’s what I did: I got some mango, some apple, some kiwi, a banana, a handful of kale, and some protein powder. Also, I went on this island vacation last year and my bartender used coconut oil in my drinks. It was delicious, so I got some of that too. Oh, and by the way, we have a blender in the kitchen already, so in almost no time, I blended all of this stuff together. So, if you want to get healthy and still drink something delicious” (places glass on table) “how about this green smoothie?”

And NOW, you again have one of two reactions, just like the first time. Unlike the first time, however, either is far more productive when the goal is to get the resounding “Yes.”

YOU SAY YES: The first outcome might just be that you say, “Why, yes, that makes total sense, thanks! This is great!” And you happily drink the smoothie.

YOU OBJECT TO SOMETHING CONCRETE: If you STILL don’t drink it, you’re at least equipped with all the information you need to have an objective and productive conversation with me. Rather than a wholesale “nope,” or a misinformed, “Meh, not for me,” you now have all the information you need to understand and communicate to me why, exactly, you’re leaning No or assuming it’s not for you.

Maybe you’d point to an ingredient you didn’t understand or don’t like eating. “Could we take out the kale? I hate how bitter it tastes.” That’s so much better for me than vague or even personal pushback!

I can say, “Sure! No problem! How about some spinach?”

Or maybe you don’t object, per se, but instead start to see opportunities to build on my thinking, which makes my thinking and thus the idea BETTER!

“Yanno,” you might say, “I see where you’re going, but I don’t think this is the right approach.” (Then, you continue to point to a specific, concrete reason as to why — because, again, I’ve given you that information). “See, the blender in our kitchen isn’t all that great. It won’t make a really smooth smoothie. What else can we try?”

Amazing, boss! Thanks for pointing that out! I’ll put together some ideas, or maybe we can talk about upgrading our blender in the company kitchen! And by the way, have I mentioned how swoll you’re looking lately?

When we discuss ideas with others in our work, we can share our thinking in a more complete way, rather than just the idea. In doing so, others never feel like they’re at an information disadvantage compared to us. Even the most powerful of leaders still doesn’t like the feeling of not knowing why your idea should exist — hence some level of skepticism in some cases. But equipping everyone around us with more information means we’ll either get the YES or, at the very least, we’ll have a productive conversation for what it would take to do so.

This may seem difficult, since it’s rather natural for us to simply share our ideas without laying out our thinking. So repeat this phrase over and over again to remember the truth:

Don’t share your ideas. Share why your ideas should exist.

Share the Why to Get to the Yes

This approach has real benefits, not least of which is we’ll continue to share ideas with confidence even after getting shot down. Why? Because we stop feeling like others don’t like US. We make the communication style less personal. By laying out our thinking, it’s no longer YOU (the judge of my idea) versus ME (the bearer of the idea).

Instead, everyone is now involved in the thinking process. In other words, we have to make others feel like cofounders of our ideas. We can put our thinking on the board and, together, discuss it and improve it. We’re both trying to solve a problem, together, and whether physically on the board or simply mentally, the object of judgment is whether this is how we should best solve a problem — not whether any one individual is “good” or “creative.”

We can stop sharing our ideas and, instead, share why our ideas should exist.

Here’s the process for doing so, ripped out of the smoothie metaphor. It means we have to act like investigators to dig up this information, whether from others or from our own thinking process.

1) What do they WANT? (Smoothie example: “Remember last week, when you told me you wanted to be healthier?”)

First, we need to state out loud that we understand what the other person wants. If they’re a CEO, they want revenue, or to build a defensible, beloved brand. If they’re a CMO, they want leads, or to create a differentiated message in the market. Or maybe not! I’m making an assumption. Step One in being persuasive is to gut-check our assumptions to understand — then articulate — what it is the other person actually wants.

We tend to hide from that. We should bring it out into the light instead. When we state it out loud as the first part of our idea pitch, we immediately align ourselves with the other person, because we’re saying up front, “Everything I’m about to say is intended to get us what you want.”

Oh really? Go on…

2) What do they BELIEVE about getting what they want? (Smoothie example: “We also laughed about how terrible most health drinks are.”)

In addition to what you want, you probably have some assumptions or beliefs about getting it. In the example here, you’ve ruled out healthy drinks as a means to be more healthy overall. Why? You believe health drinks are gross.

Maybe your boss thinks podcasting is too saturated, or that video shows require massive budgets. Whatever the case, whatever the specific belief about getting that specific desire, we need to address it in our idea pitch. Without acknowledging those beliefs, we may be aligned with the other person in terms of what we WANT … but misaligned about what that takes.

An easy example comes from my own marketing career: When I led the content team at HubSpot, executives and I both wanted us to grow a loyal audience that converted into customers. So why didn’t they buy into my ideas? I did a poor job explaining them through the lens of what they believed. They believed that short-form, SEO-focused blog posts were the best way to grow a loyal audience that converted into customers. Instead of acknowledging that, I tried to hide from that fact, telling them, “If we want to grow our audience and generate customers, we should publish more long-form content, more stories, more audio and video.”

I totally missed their bias in my pitch, so it fell on deaf ears. We believed in different paths. I didn’t acknowledge it. My idea was dead before I even voiced it.

By articulating the belief the other person already has (“health smoothies are gross”), you’re conveying to them: “Your ideas have value. You’re smart. Your opinions matter. I’ve taken them into account with what I’m about to say…”

(Note: Make sure you actually KNOW what they believe. Nothing would kill an idea quite like saying, “And I know how much you hate fun, boss! AMIRIGHT?! Huh? Boss? Why are you making that face?” But enough about the time Larry got fired…)

3) What is your REASONING? (Smoothie example: All the stuff that goes into the smoothie itself.)

Here, we can finally begin to explain ourselves more fully. We started by getting on the same page with the other person or group by articulating what they want and what they believe about getting it. We’re standing shoulder to shoulder, eyeing a problem on the proverbial board. Now, let’s try to reason our way towards a solution. The solution should include…

a) The key data.

BTW BOX #4: “Data” here does not mean “numbers.” It may include numbers, but data is just “information stored for later use.” That’s it. Data can and should also include observations you’ve made and qualitative feedback (including emotions) you’ve gathered from your audience — complement the analytics with other things. We have a wide range of data available to us today. Biases and assumptions aren’t removed until we’re willing to use all of them.

In our smoothie example, this means we listed out the fruits that obviously form the major flavor of the smoothie, but also the vegetables that add nutritional value and the protein powder that improve its … um … protein contents? (This metaphor caps out at my limited knowledge of nutrition.)

Another part of your reasoning should include…

b) Unfair advantages

Just like when I referenced adding some coconut oil to the smoothie, we can go outside our conventional norms and echo chambers to find ingredients that, once we consider them for a moment, would logically make sense for us to use. In my metaphor, I mentioned that I used coconut oil in your smoothie because I went on a tropical island vacation last year and watched my bartender use coconut oil in some delicious drinks I tried.

Whatever inspires you, even if it’s not directly related to podcasting or video, you can reference it as part of your thinking. It could be related to your brand or something that extends far outside your day to day work. Regardless, try to answer the questions: “What’s our unfair advantage or unique element here? What would make this refreshingly different? What fundamental insight have we unearthed that others overlooked? What’s the ’secret ingredient’ to make this special?”

This part is crucial, but often overlooked. Remember: You’re not simply handing them any old smoothie. You’re trying to delight the crap outta their taste buds with your idea. We don’t want to make “yet another a show.” We want to impress the hell outta the audience and create passionate superfans that love us and trust us and buy from us and can’t stop talking about us because HAVE YOU HEARD ABOUT THIS AWESOME SHOW THEY MAKE?!?!?

(Take a breath, Jay. Take a breath…)

We don’t just care about the letter of the law: the basic ingredients. We care about the spirit. We want to do exceptional work, so we better pull from what makes our experience of the world an exception. Complement the key data with your opinions and intuition when sharing your reasoning behind your idea, the green smoothie you want others to drink.

Lastly…

4) What RESOURCES do we need? (Smoothie example: “Oh, and by the way, we have a blender in the kitchen already, so in almost no time, we can blend all of this stuff together.”)

At this point, we’re aligned around what they want. We’ve acknowledged their beliefs about how to get it. We’ve laid out our reasoning, including both the key data and our refreshing twists that give us an unfair advantage. We’re almost at the last remaining question in others’ minds: “So what’s this gonna cost me/us?”

Rather than leave that to their preconceived notions or rely on social proof, like case studies, to justify the investment … actually answer that question up front. They’re now so interested in where this is going that they’re thinking, “How can we do this?” instead of, “How will this cost us?”

What resources do we need? Budget, time, team, knowledge, permission. There are all kinds of ways to make this more palatable for a decision-maker you’re talking to. For instance, if you’re trying to make a show, focus on developing the concept, buying some basic tools, and crafting a pilot. After that, you can worry about getting full buy-in for a scarier-sounding amount of money (because, by then, they and you will have more information to make a better decision).

If that won’t work, find budget that’s being used but poorly. “Hey, we’re running all these banner ads and buying offline ads in print media. Do we know how that’s doing for us? That’s brand ‘awareness’ stuff, isn’t it? What if we focused less on passive awareness and made something that generated proactive, engaged affinity for our brand instead? Let’s carve some budget from that and apply it to this.”

By now, we’ve covered a lot of information, even if this all took two minutes to say:

- They know we’re aligned on what they WANT and have considered what they BELIEVE about getting it.

- They understand our REASONING — both the key data and our potential unfair advantages.

- They understand what RESOURCES we need.

- And here, and only here, can we finally reveal our actual idea…

5) REVEAL THE IDEA

So … if you want to be healthy, but you’ve had a bad experience with all those other health drinks out there, then… BOOM … here’s a green smoothie. Wanna drink it?

So … if you want to build a brand that helps us drive results, but you’re not sure about all those “brand awareness” things marketers usually do, then … BAM … this show. Wanna make it?

Look, I get it: This feels like more work, and maybe at first, that’s true. At first, you may find yourself carefully thinking through your talking points or reflecting on how you arrived at an idea that felt like it just hit you. At first, you might hesitate to lay out your thinking on the table like that, for fear of being vulnerable, or you may feel too eager to jump right to the idea itself. But I promise you, the more you communicate like this, the easier it flows. It becomes muscle memory.

If you want to make the case for making a show for your brand, whether you report to the CEO or a marketing leader, sell ideas to your team to inspire them or your clients to get buy-in, we all need to improve the way we share our ideas. Remember: Don’t share your ideas. Share why your ideas should exist.

Avoid the green smoothie problem. Close that information disadvantage by giving others the information they need. Then and only then are we ready to ask, “Wanna drink it?”

If we did, maybe we’d finally get the reaction we actually want in our quest to make great shows:

“That was great! Can I have some more?”

Founder of Marketing Showrunners, host of 3 Clips and other podcasts and docuseries about creativity, and author of Break the Wheel. I’m trying to create a world where people feel intrinsically motivated by their work. Previously in content marketing and digital strategy at Google and HubSpot and VP of brand and community at the VC firm NextView. I write, tinker, and speak on stages and into microphones for a living. It’s weird but wonderful.

Get in touch anytime: jay@mshowrunners.com // Speaking inquiries: speaking@unthinkablemedia.com

Great insight, Jay. I’ve done this well and poorly without really thinking about it either time. Thanks!

Thanks, Kevin! Glad it resonated, and agreed — so helpful to have terminology and process to enhance and repeat creative success, not hinder it. Wish I embraced that idea sooner in life!